La couleur du temps

Tunis (Tunisia) October 3-10 2017

Erin Manning

Dream City, Tunis Octobre 2017

La couleur du temps

Il y a une odeur au delà de la couleur, un toucher dans le regard, un goût dans la texture. Quelle est cette qualité qui dépasse la première approche à un objet, la qualité qui passe par la forme d'un objet mais qui transperce l'expérience, qui ouvre un objet à sa force? Comment parler de la durée qui rayonne au delà de cet objet? Comment toucher le faire-oeuvre de l'oeuvre, son mouvement implicite?

Un objet ne peut jamais être complètement cadré. On ne peut jamais complètement le cerner. Pas seulement parce que l'objet résiste à une perception générale - sa transversalité ne peut être réduite à l'expérience d'un seul témoin - mais parce que l'objet porte aussi, lui-même, la couleur du temps. Cette couleur est synésthésique: elle déborde d'un sens prédéterminé qui souhaiterait le localiser dans le temps.

L'objet n'est donc jamais tout à fait "lui-même." Il est relationnel, écologique. Il participe, comme le dirais Isabelle Stengers, dans une écologie des pratiques. Et il redonne un sens, une direction, aux écologies qu'il co-compose.

Cette description de l'objet s'ouvre au concept du geste mineur. L'objet vibre de gestes mineurs potentiels. Ces gestes mineurs sont ce qui invite l'objet à s'ouvrir vers sa transformation, à sa variation interne.

Ce que je propose pour Dream City est un geste mineur qui oriente la couleur du temps. Ce geste mineur sera activé par une pratique dans le temps qui aura commencé durant mon séjour à Tunis.

Durant mes 10 jours à Tunis en avril 2017, à la recherche de tisserands, je me suis trouvée dans un rituel de commerce. Les soies, après tout, sont nées d'un commerce qui a orienté la navigation et créé des géographies d'échange, un commerce aujourd'hui presque perdu parce que le fil de soie est trop cher et le travail du tisserand trop ardu. Donc aucune question que la négotiation pour l'achat de la soie est aujourd'hui encore un geste capitaliste. Mais ce qui m'a touché dans la médina de Tunis, où la majorité du commerce tourne autour des produits provenant de Chine, était la qualité de la rencontre avec le tisserand. Le commerce était dans le temps - le temps de prendre connaissance, le temps de communication, le temps de toucher le textile, et d'en toucher un autre. De prendre un thé et de discuter le voile que portera la mariée. Le temps de parler de mon métier, et de la richesse que je ressens si profondément autour de la production du textile, de la main d'œuvre, de la tradition. Et la surprise de mon geste contemporain, la folie de tirer des fils, de défaire la toile.

Ce commerce a aussi une dimension alter-économique. Il propose un mode de rencontre qui touche à la création d'une certaine valeur. Ensemble on partage la reconnaissance que ces arts presque perdus ont une énorme valeur. Pas question de négocier le prix. Il n'y a pas de prix qui serait juste. Et donc on ne parle que très vite du prix. Au lieu on parle du retour, du projet, du mariage qui aura lieu. On parle des qualités de fil, des couleurs. J'achète 2 soies, un cotton, celui-là tissé en dehors de la médina mais vendu à côté de la mosquée Zitouna, où il y a encore quelques touristes. Je reçois un cadeau. Parce que finalement ce métier ne peut pas être acheté, ni vendu. Il ne persistera que par amour pour ce qui est au délà de l'objet-même, la couleur qu'il donnera au temps.

Je quitte Tunis le 17 avril 2017 pour continuer l'exploration du temps au Bauhaus, à Weimar, où une des artistes du textile les plus importantes a commencé - Annie Albers. Ce sont ses mots que j'entend: le textile, dit Albers, est la première architecture. Et c'est ce qui rend possible le chez-soi. L'art du textile, pour Albers, est ce qui n'est jamais perçu comme objet mais comme ce qui permet à un espace de prendre forme.

Ce travail dans le temps continuera maintenant pour 5 mois. Tous les jours je travaillerai avec 3 morceaux de tissus - 2 soies, 1 cotton. Mesurant 2.4 x 2 mètres, ce sont des morceaux larges et presque carrés. Le travail sera long et répétitif. Je tirerai les fils, et, une fois le textile assoupli, je lui redonnerai une épine dorsale et réinsérant ses propres fils.

Ce travail sera un travail patient. Il créera sa propre chorégraphie, une chorégraphie qui un jour se retrouvera, j'imagine, dansé. Mais pour le moment, je n'essaierai pas de le cerner, mais plutôt de le sentir. Cette sensation de travailler à partir du mouvement des fils eux-mêmes sera portée par un désir de suivre un processus qui se déroule dans le temps. Les gestes qui émergeront seront sûrement influencés par les contours de la médina, par les géométries de ses tuiles, par ses sentiers étourdissants. Comme dans la médina elle-même, je suis certaine qu'il aura des moment où je perderai mes repères. Le textile gardera le souvenir de toutes ces durées, et ce sera cette couleur du temps qui reviendra à Tunis on octobre 2017.

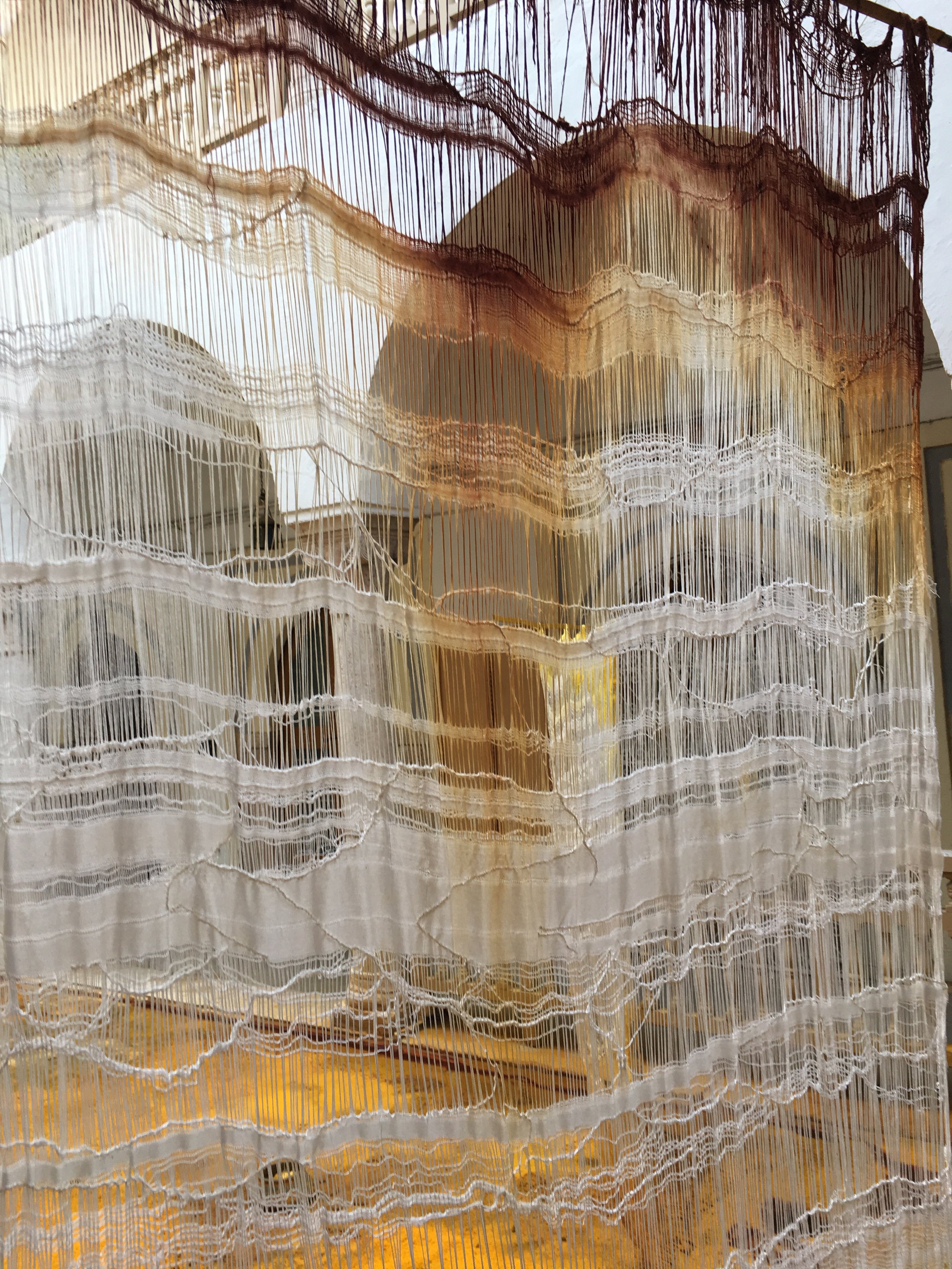

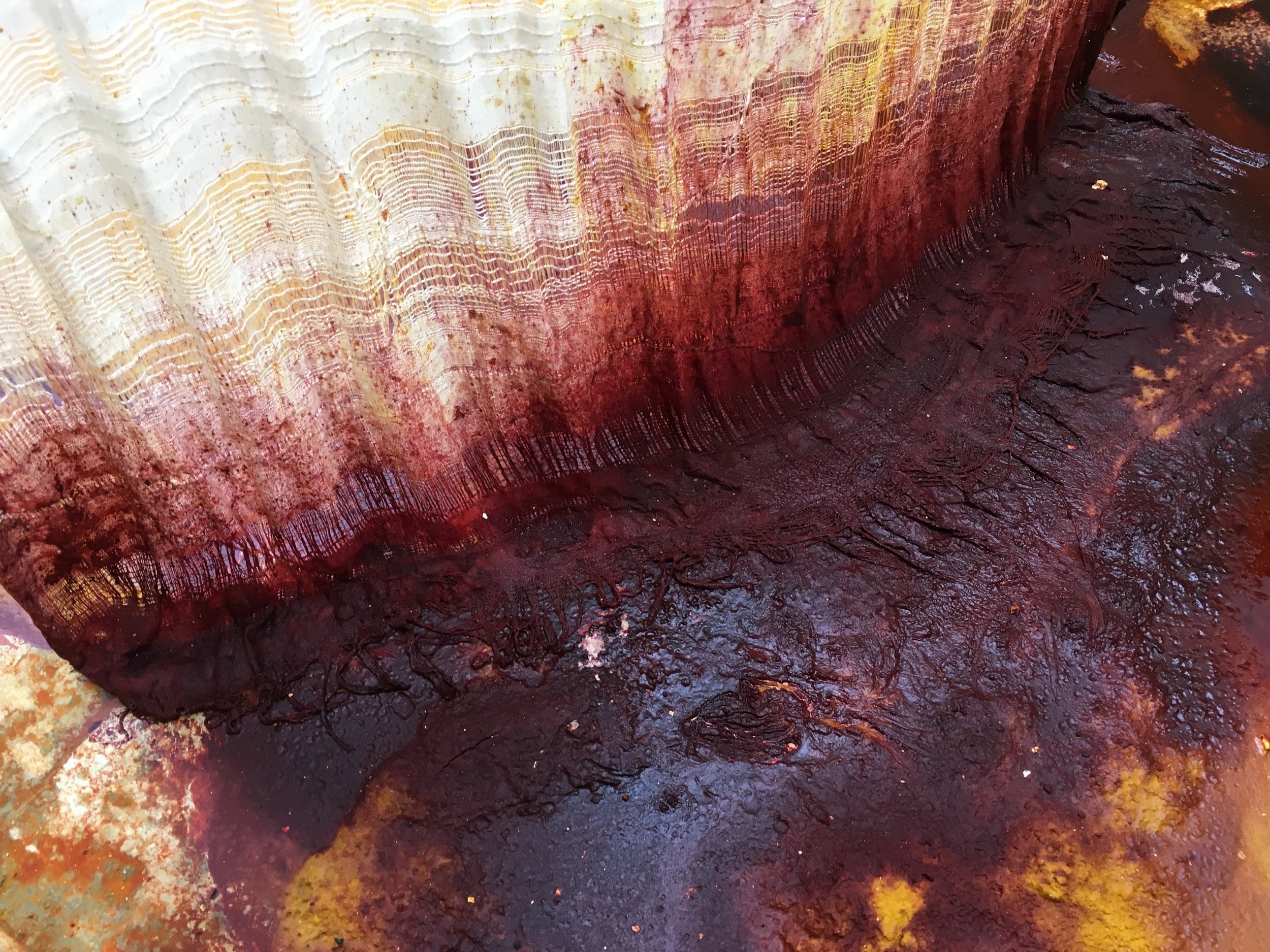

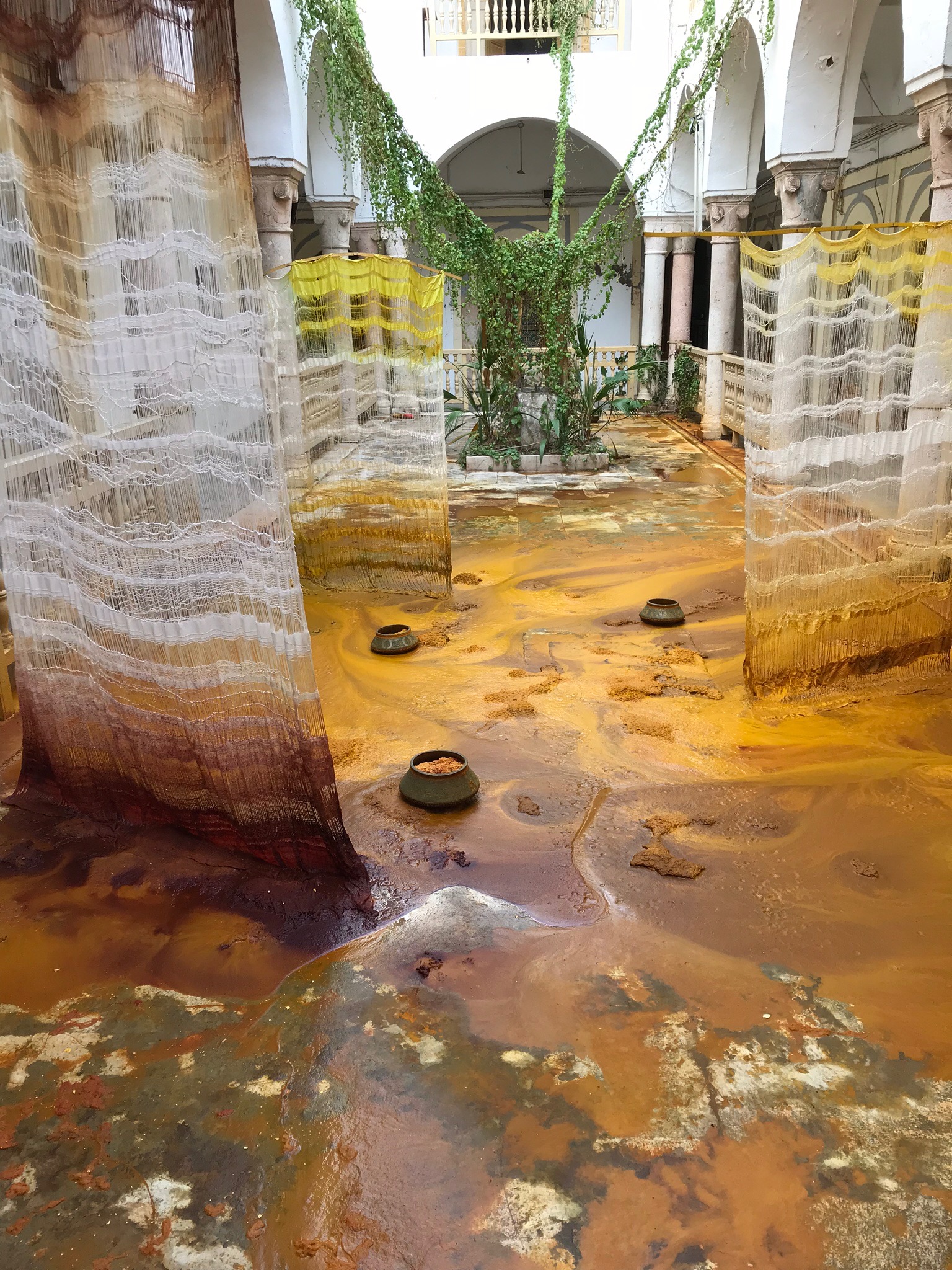

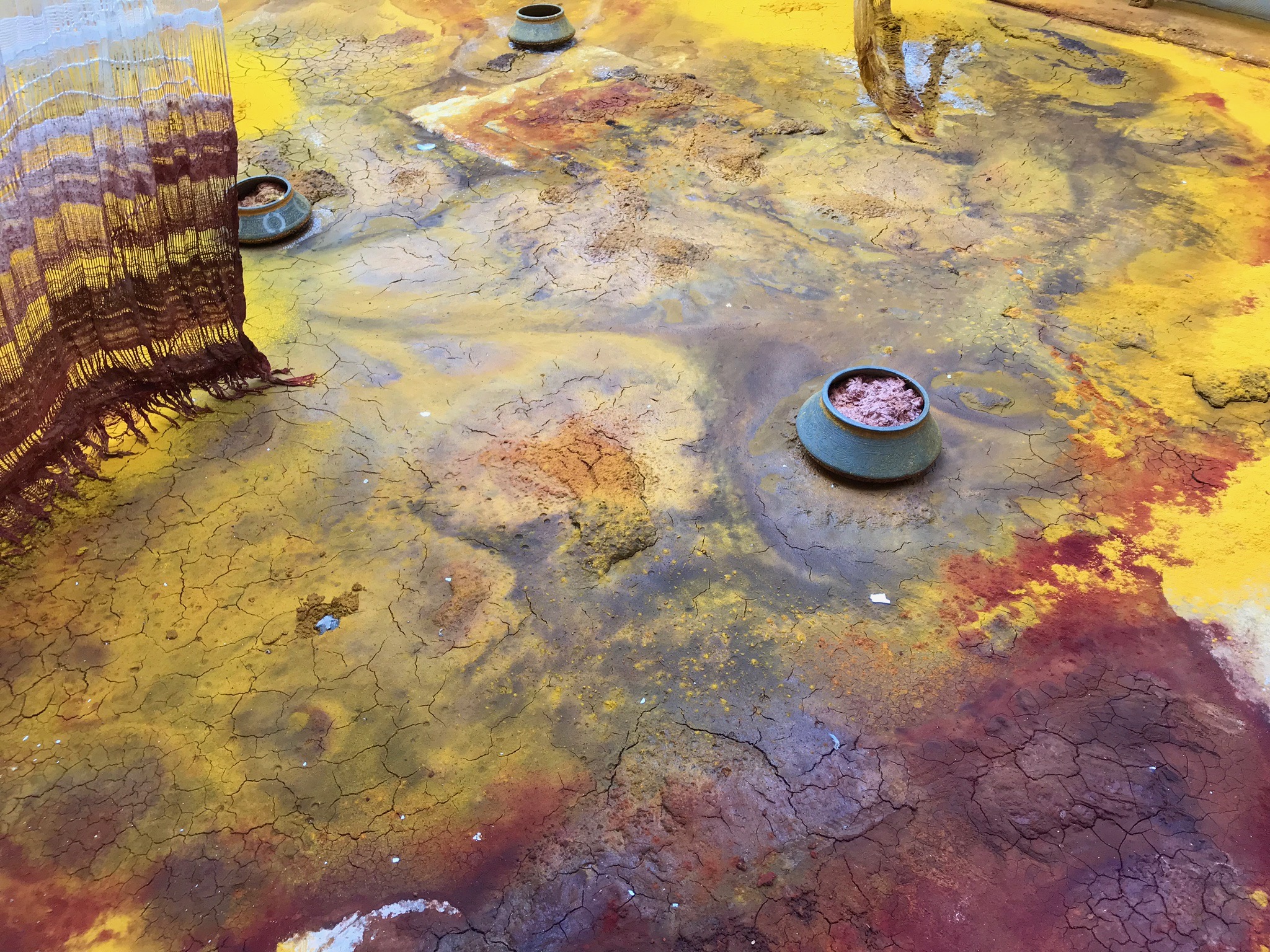

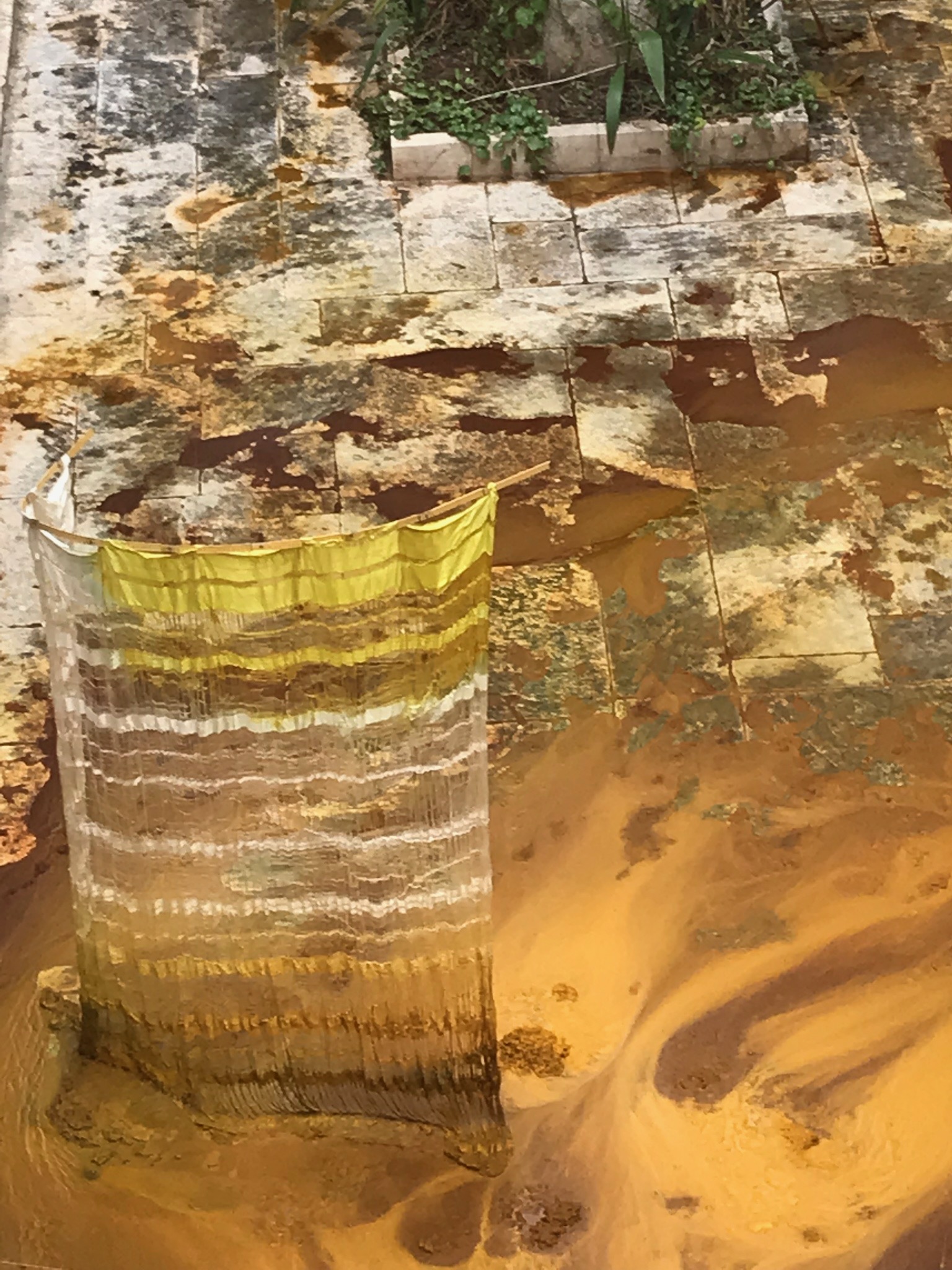

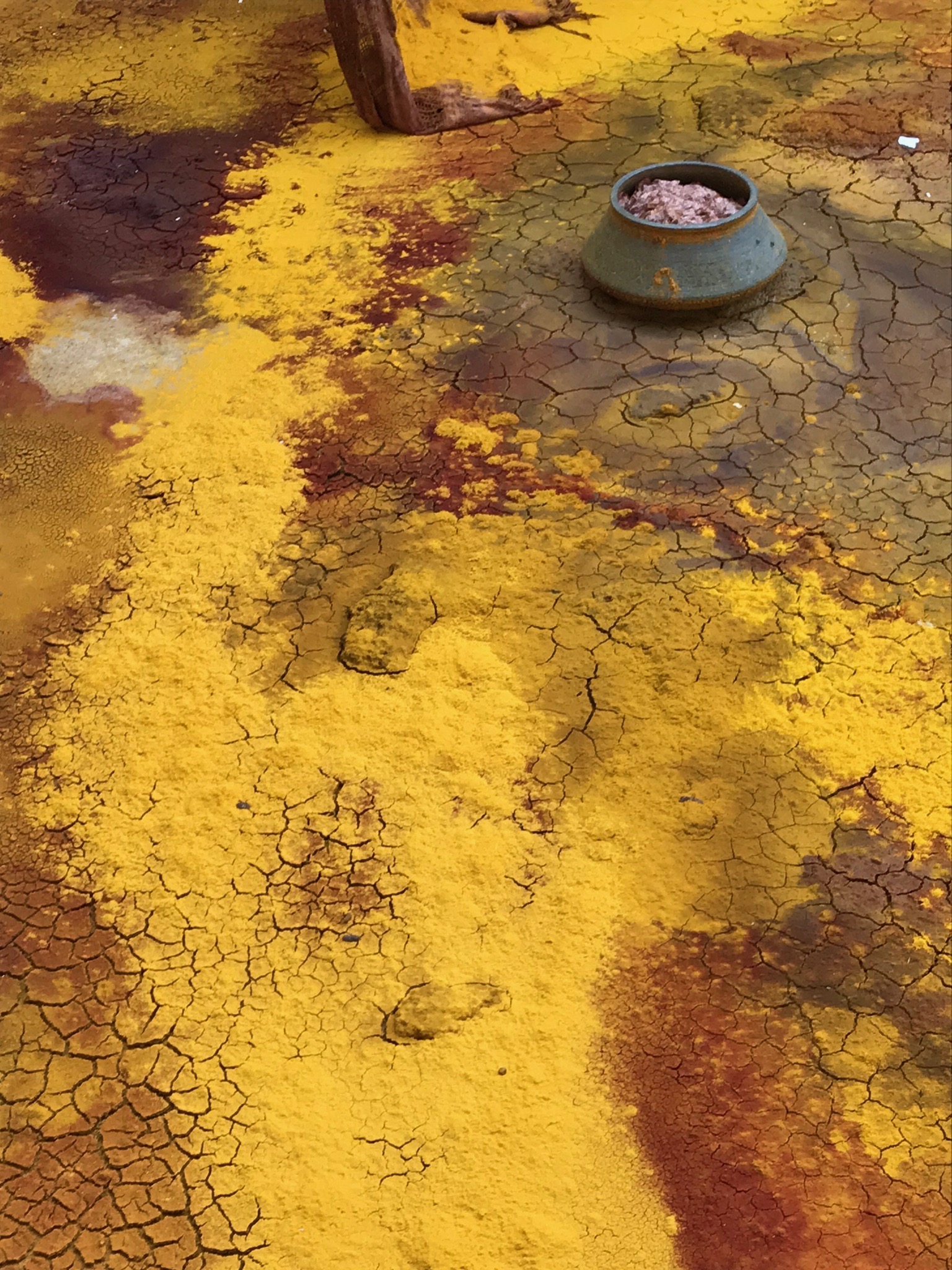

Arrivée à Tunis, les 3 toiles seront pendues dans le lieu convenu. Très larges elles occuperont presque toute la largeur du lieu et seront pendues pour que le spectateur doive se laisser toucher par elles si il ou elle veut passer. Il y aura 2 bancs en bois installés des 2 côtés du passage. Le sol sera recouvert de curcuma. La toile aussi sera arrosée pour qu'elle puisse prendre la couleur de l'épice. La couleur du temps deviendra parfumée par une des odeurs, un des mélanges, de la médina.

Les textiles prendront de la couleur en même temps qu'ils s'assoupliront, parce que l'arrosage donnera aux toiles une certaine lourdeur. Doucement, on sentira les effets de la gravité, et avec eux, les effets de l'environnement - le soleil, le vent, la tombée de la nuit.

Les gestes mineurs ne peuvent ni être créés ni être mesurés à l'avance. Bien qu'ils soient toujours là en potentiel, ils restent souvent inactivés. Impossible de savoir aujourd'hui comment et si les gestes mineurs se proposeront dans le cadre de Dream City. Ce que La couleur du temps offre est un rideau de tulle qui peut-être saura capter ce qui reste trop souvent imperceptible, et, par extension, dévalorisé. Si il y a valeur dans ce projet qui essaie de toucher la texture du temps, ce sera une valeur découverte dans le cadre d'une participation autant avec un public se promenant dans la médina qu'avec la complexe écologie des pratiques qui s'inventent, de jour en jour, dans la médina elle-même. Parce que cette oeuvre n'existe pas pour faire revivre le passé qui se perd mais pour célébrer ce qui vibre au-delà de l'expérience comme on la connait, ce qui ne peut jamais complètement être cerné par les regards qui cherchent à catégoriser l'existence.

An odour of colour, a touch in the gaze, a taste in the texture. What is this quality that exceeds the first approach of an object, the quality that moves through the form of an object but pierces experience, opening the object to its force? How to speak of the duration that radiates beyond the object? How to touch the becoming-work of the work, its implicit movement?

An object can never be fully determined. Not only because the object resists a generalized perception of itself – its transversality cannot be reduced to the experience of a single witness – but because the object also carries with itself the colour of time: it overflows category, altered by every encounter.

The object is never completely itself. It is relationnal, ecological. It participates, as Isabelle Stengers might say, in an ecology of practices. It gives sense back, gives direction, to the ecologies with which it co-composes.

This description of the object opens itself to the concept of the minor gesture. The object vibrates with potential minor gestures. These minor gestures are what invite the object to open itself toward its transformation, toward its internal variation.

What I propose for Dream City is a minor gesture that orients the colour of time. This minor gesture will be activated by a practice in time that will have started during my time in Tunis in April 2017.

During the 10 days I spent in Tunis in April in search of weavers, I found myself in a ritual of commerce. Silks, after all, spawned a commerce that oriented navigation for centuries, creating geographies of exchange. While the commerce as it was known during the period of the silk road is almost nonexistent today – due to industrialization and the prevalence of synthetics, which are far less costly –there is no question that the negotiation for the purchase of silk remains today a capitalist gesture. And so to travel to one of the sites of the earlier trade, and to seek out the few weavers left in order to purchase silk, would have to be seen as a gesture of capital.

Whereas my earlier work Threadways focused on ubiquitous mass-produced industrial textile and sought to explore the paradox of subtraction in the context of neoliberal capital, the Tunisian project of seeking out hand-loomed silks and cottons arguably placed me back squarely in the marketplace. Rather than resisting this gesture, I became curious about it. What can an economic exchange produce in the context of an artistic process?

What touched me in the medina of Tunis, where the majority of commerce circulates around products from China, was the quality of the encounter with the few remaining weavers. The commerce took place in time – the time of the encounter, the time of communication across languages, the time of touching the textile, of feeling its weave. The time of sharing a glass of tea and of discussing the veil to be worn by the bride. The time of speaking of my own work, and of the richness I sense so profoundly regarding the production of the weave, the handiwork, the tradition. And the surprise of my contemporary gesture, the madness of pulling the thread, of unweaving the textile.

This commerce contains an alter-economic dimension. It proposes a mode of encounter that touches the creation of a certain kind of value. Together we share the recognition that these almost lost arts are of enormous value. No question of negotiating the price. There is no price that would be right. And so we barely speak of price. We speak instead of my return, of my project. We speak of the quality of the thread, of the colours. I buy two silks, each woven by a different older man, one of the 5 remaining weavers in Tunis, and one cotton, this one woven outside the medina sold next to the Zitouna mosque where there are still a few tourists. I receive a gift. Because finally this professsion cannot be bought, or sold. It will persist only through a care for what is beyond the object itself, the colour that it will give to time.

I left Tunis the 17th of April 2017 to continue the exploration of time at the Bauhaus, in Weimar, where one of the most important textile artists began her work – Annie Albers. Her words are the ones I hear: textile, says Albers, is the first architecture. It is what makes home possible. The art of textile is what can never be perceived as an object as such. It is what gives space quality of form.

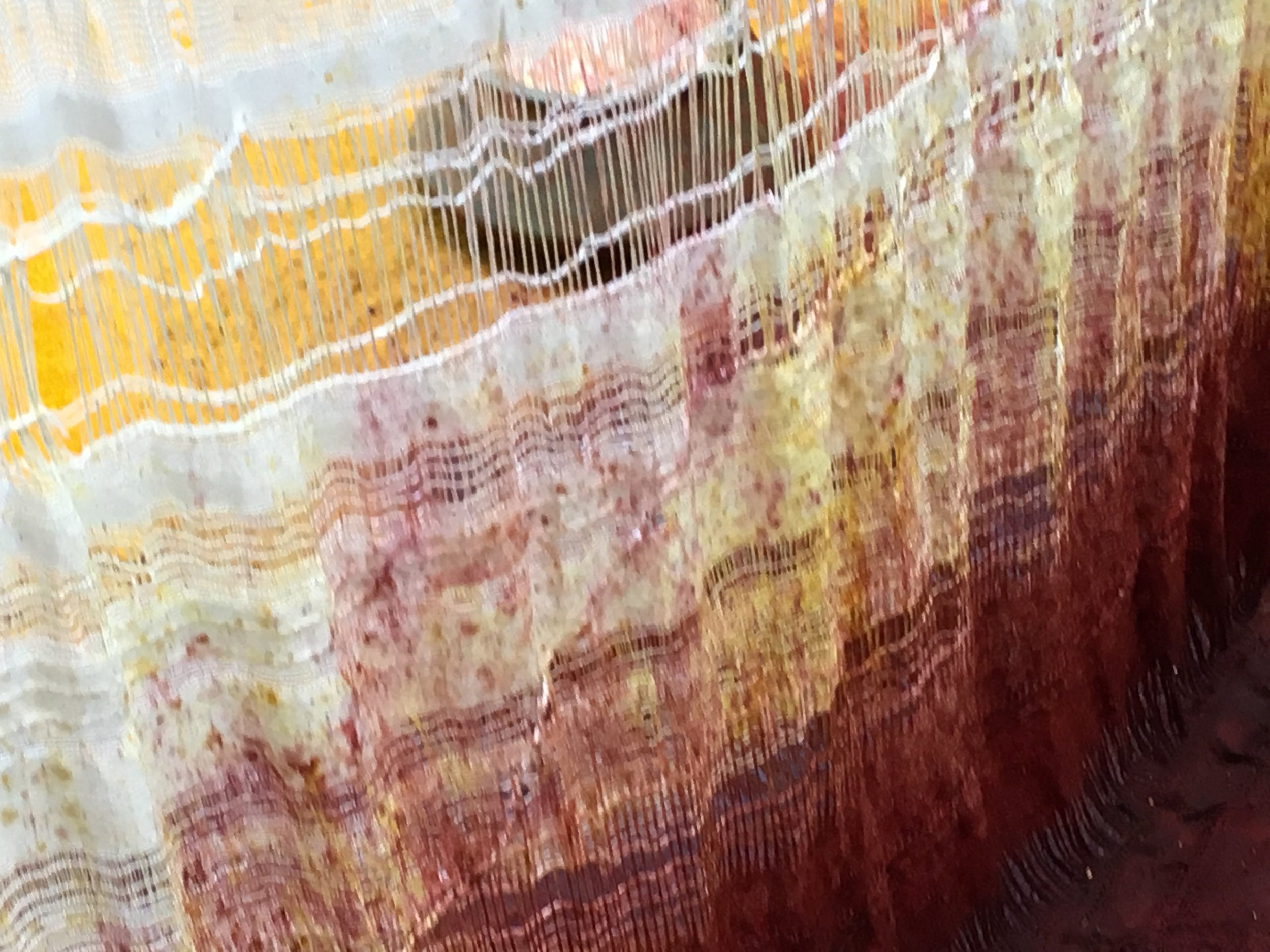

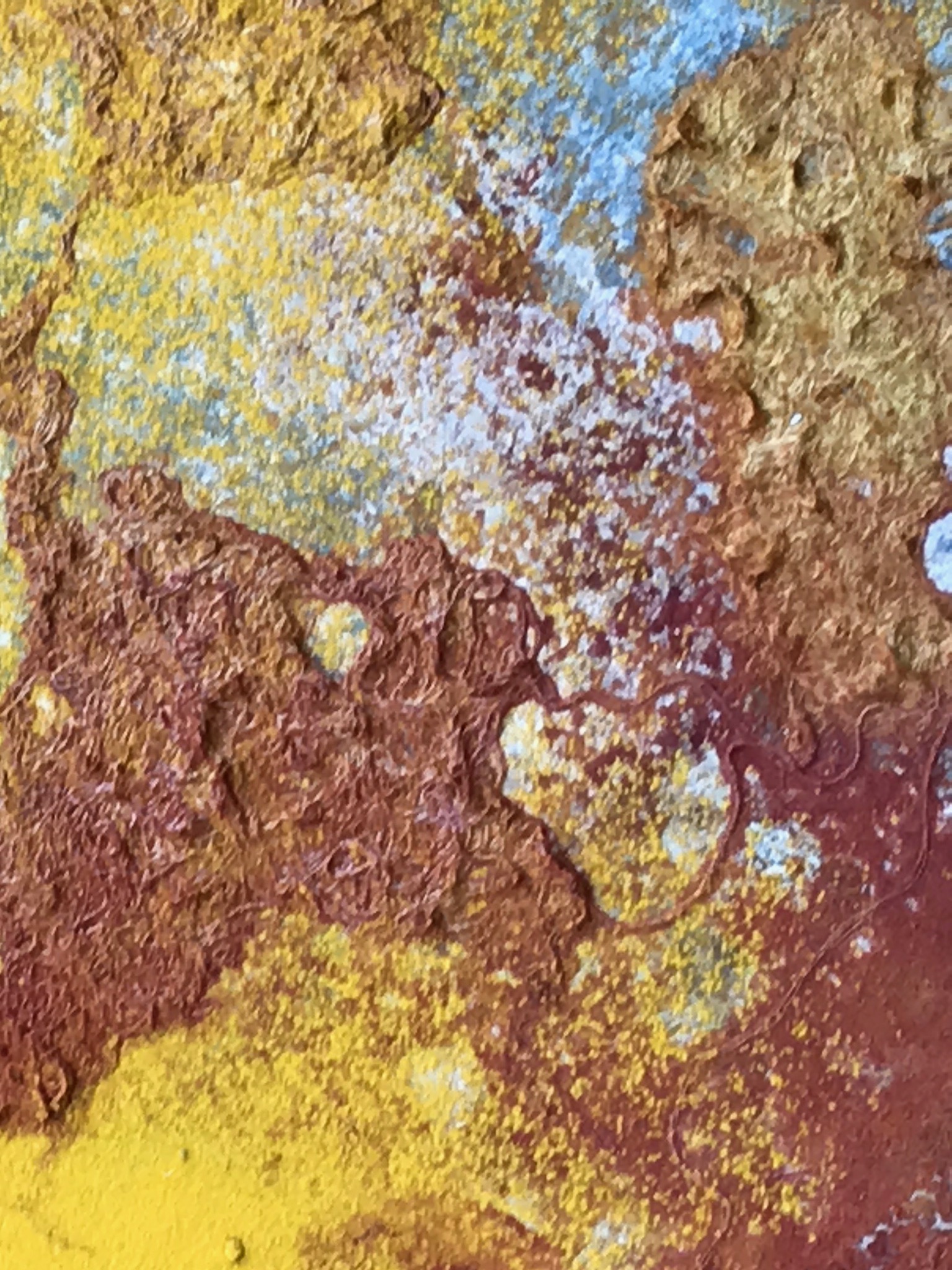

This work in time continues until October. Every day I work with the three textiles. Measuring 2.4 meters by 2 meters, these are large, almost square pieces. The work is long and repetitive. I pull the threads, always on the warp, and once the textile loosens, once it can barely hold its shape, I give it back its spine by reinserting its own threads, threads dyed using a Tunisian turmeric. The colour of the threads shifts with the natural mordants I use when I mix the spice into dyes. The smell with the variations in colour mark a synesthetic differential that moves through the textile.

This is patient work that creates its own choreography, its own dance. The aim is not to control the textile but to move with it, following its own tendencies. This sensation of working from the thread itself is carried by a desire to follow a process that unfolds in time. The gestures that emerge are influenced by the contours of the medina, by the geometries of its tiles, by its dizzying pathways. And by the movements of Weimar, the time of its own textile history which haunts me as I pull the threads. The textile in its slow unweaving holds the memory of all these durations, of the sense of direction proposed in the pulling. It is this colour of time that will return to Tunis in october 2017.

Upon arrival in Tunis, the three textiles will be hung. They will occupy almost the full width of the site such that the participant will inevitably be touched by them when walking through. There will be two wood benches, installed on the two ends of the passageway. Below each textile, there will be a small aluminium pot. Each pot will be filled with one of the spices, reflecting the dyeing of the threads. A few threads will hang in each pot. Water will be added to the spices in the pot each day and the textile will be sprayed to facilitate the colour leaching up the threads. The colour of time will become scented by one of the odors, one of the mixtures, of the medina.

The textiles will take the colour at the same time as they become more supple – the spraying will give the textile a certain weight. Slowly, we will feel the effects of gravity, and with them, the effects of the environment – the sun, the wind, the falling of the night.

Minor gestures can neither be created nor measured in advance. Even if there in potentia, they often remain unactivated. It is impossible to know today how and whether minor gestures will propose themselves within the framework of Dream City. What The Colour of Time offers is a mesh curtain that will perhaps know how to gather what too often remains imperceptible, and, by extension, devalorised. If there is value in this project that aims to touch the texture of time, it will be a value discovered in the complex ecology of practices that invent themselves, day by day, in the medina itself. Because this work does not exist to reenliven a past that is becoming lost but to celebrate what vibrates beyond experience as we know it, to celebrate what can never fully be discerned by the gaze that seeks to categorise existence.